Article

Arbitrary Arbitration: Dwelling into the Question of the Addition of the IV Schedule Amid Ginormous Cost of Judicial Adjudication

Mohit Singhvi and Madri Chandak seek to understand the efficiency and application of the IV Schedule to the Arbitration and Conciliation Act (hereinafter referred to as “the Act”) and bring into light the justifications behind addition of such schedule and also the burning question of such exorbitant fee of delivery of justice and its reach to the financially challenged.

-

Mohit Singhvi

Mohit Singhvi

-

Madri Chandak

Madri Chandak

WHAT DOES THE LAW SAY?

The recent changes in the Act in 2015 and 2019 have tremendously affected such procedures of arbitration. One of such changes is the provision of fees of arbitrators, which has been demarcated in the newly-added IV Schedule. Even earlier, the 246th Law Commission Report1 had deliberated a model schedule of fees for arbitrators. The Commission had relied on Union of India v. Singh Builders Syndicate2, wherein absence of celling on fee for arbitrators was discussed.

In 2015, the Act was amended3 (“2015 Amendment”) and Schedule IV was added to the Act. The Schedule was inserted with an object of providing a model fee-structure for domestic arbitration with the grundnorm intention to put a bar on the havoc created by humungous fee charged by the Arbitrators which largely depended upon the quantum of the claim. Accordingly, relying on this model fee-structure, the High Courts were given the authority to frame rules to determine the fees of Arbitral Tribunal, where a High Court appoints an arbitrator under Section 11 of the Act. Section 31 (8) was added to the Act which lays down that the costs of arbitration shall be calculated according to Section 31A (Regime for costs). It also mentions that the costs constitute “reasonable costs” for the following:

- the fees and expenses of the arbitrators and witnesses,

- legal fees and expenses,

- any administration fees of the institution supervising the arbitration, and

- any other expenses incurred in connection with the arbitral proceedings and the arbitral award.

Additionally, according to 31A (1)(b), the determination of amount of costs falls back on the discretion of the Court OR the arbitral tribunal. However, certain ambiguities prevailed in the 2015 Amendment and therefore, when the Act was further amended in 20194 (“2019 Amendment”), new changes were introduced with respect to fees being charged by arbitral tribunals.

2. (2009) 4 SCC 523.

3. The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015, No. 3, Acts of Parliament, 2016 (India).

4. The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019, No. 33, Acts of Parliament, 2019 (India).

The 2019 Amendment provided for establishment of arbitral institutions and such arbitral institutions were defined as “an arbitral institution designated by the Supreme Court or a High Court under this Act”. Consequently, the 2019 Amendment made Schedule IV mandatory for domestic arbitrations, where the appointments were being made under Section 11. Given the 2019 Amendment, the High Court is not required to notify the rules. The High Court will now be designating arbitral institutions to discharge all the necessary and proper functions which will include appointing arbitral tribunal and fixing its fees.

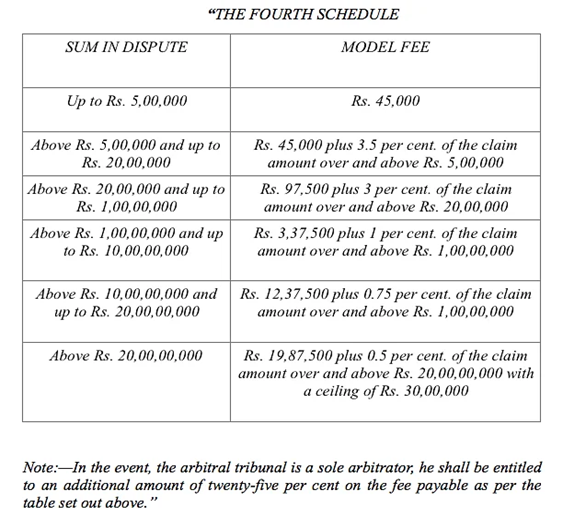

Looking at the IV Schedule, a fee structure has been laid down for the arbitral tribunal, solely based on the amount of claim. It further mentions that the maximum amount which can be charged is INR 30,00,000 in case of appointment of two or more arbitrators and INR 37,50,000 in case of appointment of a sole arbitrator. The schedule has been appended below:

The IV Schedule brings along with it several debatable questions. A few of them being: when is the IV Schedule applicable and whether the determination of fees of the arbitral tribunal on the basis of sum in dispute justified?

MANDATE OF THE SCHEDULE IN QUESTION

Looking briefly at the first question, there is a dispute on whether Schedule IV is mandatory or just directory. Recently in 2019, in the case of National Highways Authority of India and Ors. v. Gayatri Jhansi Roadways Limited and Ors.5, the Apex Court noted that the IV Schedule will not be mandatory where the fees had already been determined by an agreement between the parties. This is a remarkable judgment since it enhances the principle of “party autonomy” and distinguishes the cases where the fees had already been agreed upon from those cases where the fees is yet to be determined. Additionally, it infers to the fact that in regards to payment of fees, the discretion of parties shall prevail over the statutory provisions.

Earlier, in cases before the Patna HC6 and the Delhi HC7, the Court noted that the IV Schedule had to be complied with and the limit set therein cannot be breached. However, the Delhi HC had also given a contrary position in GS Developers8 wherein it observed that, “The Fourth Schedule to the Act being merely a guiding model, is not binding on the Arbitrator specially because the same has not been so far been adopted by this Court in its Rules. The Arbitrator was, therefore, free to determine his own fee.” In Paschimanchal Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited v. IL&FS Engineering & Construction Company Limited9, the court did not interfere with the fees of the arbitral tribunal since the tribunal was not appointed by the court and the constitution took place according to the mutual agreement of the parties.

Conclusively, there are three scenarios:

- Where the appointment has been done in accordance with the agreement of the parties, the IV Schedule will not be applicable and the court shall not interfere with the payment terms.

- Where the appointment has been made by the court but there is an existing agreement on the amount and payment of fees, such fees shall only be paid, irrespective of the IV Schedule.

- Where the court has done the appointment and no terms of payment have already agreed upon, the IV Schedule has to be complied with. According to majority opinion, the IV Schedule has to be followed irrespective of whether the High Court has notified the rules or not.

6. Kumar and Kumar Associates vs. Union of India, 2016 SCC OnLine Pat 9476.

7. DSIIDC Ltd. v. Bawana Infra Development (P) Ltd., 2018 SCC OnLine Del 9241.

8. G.S. Developers & Contractors Pvt. Ltd. vs. Alpha Corp Development Private Limited and Ors., 2019 SCC Online Del 8844.

9. 2018 SCC OnLine Del 10831.

However, certain ambiguities still prevail. On the one hand, the legislation intends to universalize the fee structure and on the other hand, the 2019 Amendment proposes establishment of arbitral institutions and not all institutions follow the IV Schedule. Also, the judgment in GS Developers tends to create confusion since even the court-appointed arbitrators think of the IV Schedule as a “guiding principle”.

THE LOGIC BEHIND THE IV SCHEDULE

It is common knowledge that “reasonable costs”, as mentioned under Section 31(8) of the Act, are seldom overlooked and the entire arbitration becomes highly expensive. The costs includes fees as well as expenses and whatever the breakdown of the entire costs may be, it does empty the pockets of people who chose arbitration for its ease. The legislation has made an attempt to regulate such costs, especially the fees taken by the arbitrator. But one needs to contemplate on how effective this regulation, solely based on the quantum of the amount in dispute, is?

The mechanism to regulate the fees of arbitrators fails to take into consideration the fact, that increase in sums in dispute does not guarantee increase in complexity of the case. A claim in a dispute may be too high and yet not so complex to adjudicate. However, even in such cases, a prescribed fee in the IV Schedule sets a minimum and maximum limit. Even in cases involving a comparatively less sum in dispute, the added costs of engaging counsels leaves the party in dejection. In light of this, it is pertinent to look into Article 39(1) of the Swiss Rules of Arbitration. It states,

“The fees of the arbitral tribunal shall be reasonable in amount, taking into account the amount in dispute, the complexity of the subject-matter, the time spent by the arbitrators and any other relevant circumstances of the case, including, but not limited to, the discontinuation of the arbitral proceedings in case of settlement or other reasons. In the event of such discontinuation, the fees of the arbitral tribunal may be less than the minimum amount resulting from Appendix B (Schedule of the Costs of Arbitration).”

Mr. Fali S. Nariman very rightly stated, “Giving the appearance of justice to a party is as important as administering of justice itself”.10 A person may win a case and feel that justice has been served but once he starts to do a cost-benefit analysis in arbitration, such administered justice may also go into waste. Therefore, a straight jacket formula, premised on the amount on sum in dispute, may be suitable for a few arbitrations but not for all and also the dependency of the quantum of claim seems to be really unreasonable. This is also required to be looked into from the perspective that while the same Arbitrator was delivering justice as a judge of the Hon’ble Court and dealing with largely complex matters, both on facts and law and pressure of the highest amount of burden relating to pendency of cases, the quantum of amount involved was never taken into consideration. Arguendo, the moot question which has gone unattended is that does justice becomes so expensive the moment the seat changes, the cost of adjudication becomes unreachable frustrating the entire effort of quick resolution of disputes.

Moreover, two scenarios are possible, either we treat the arbitrators as judges or we treat them as professionals. Providing financial benefits for arbitrators, by considering them as judges, is not feasible for the government. Also, the arbitrators do not serve the public like the judges and therefore, there is no reason why government should provide salary to them. Looking at the contrasting position, if we consider the arbitrators as professionals, there are several professions such as Architects, Chartered Accountants and Advocates, whereby their governing bodies have refused to put a cap on their professional fees.

This also brings into light the existing contentions on whether ex-judges should be appointed as arbitrators? These are the same judges who perform judicial and adjudicatory functions with repute in courts. However, when they take their seat as arbitrators, another set of privileges, especially with regards to financial benefits, gets added to them. The matters involving high stakes may or may not involve huge claims of money but they have set a standard of arbitrators to be appointed. Such standard is often topped by ex-judges. Another set of disturbing trend is the appointment of counsels even when questions of law are not involved. This has inculcated advocacy and judicial norms even in processes of “alternative” dispute resolutions.

It is an ethical duty on behalf of judges and lawyers to be disassociated from the subject matter of the case, the amount of claims in dispute and the parties involved. However, when the fees of arbitrator gets statutorily connected to the amount of claim, one cannot expect such disassociation. Additionally, holding or acquiring a financial interest in the subject matter of a case affects independence of the adjudicators. Ibrahim Adilshah told Ferishta once, “write without fear or flattery… if a writer is influenced by these unworthy and unmanly emotions and motives, his work becomes not only dishonest, but insipid, humdrum and featureless?” One cannot undermine the fact that financial benefit is no less than flattery and when it comes to adjudicators, flattery is indeed deceitful.

Justice Dorab Patel (of Pakistan) mentioned once, “In the long run the manner in which judges and lawyers discharge their duties can build up public opinion and public opinion is a better safeguard for the independence (of judges and lawyers) than any law or constitutional guarantees?”11 It cannot be denied that the public opinion in regards to these mandates of fees taken by arbitrators is worsening every day and when such safeguard shall fall, the trust on all modes of Alternative Dispute Resolution will also break.

Yet another interesting factor is the summing up of the claim and counter claim for reaching to the fee of the Arbitrators and then dividing the same equally between the parties for making payment to the Arbitrator. This issue becomes imperative when one of the parties in order to frustrate or terrify the other party files a claim without any substance which ultimately makes it compulsory for the other party to bear the cost without per se having any choice of dissent thereby substantially involving the amount of money to be paid, may be recoverable at a later stage.

CONCLUSION

India has taken up several measures to move towards setting up of international standards for arbitration. However, several loopholes, in regards to appointments and payments of arbitrators, do exist. In this regard, the authors believe that the regulation of fees, solely based on the quantum of claim, is unjustified. Several other factors affect the functioning of arbitration proceedings and one should not impose a minimum-maximum bracket in relation to the subject matter of the dispute and the legislature must ensure that legal costs are reduced, in order to enable justice reach more efficiently and fairly and to the mass.

Undoubtedly, arbitration is getting expensive every day and the authors do believe that the mechanism has to be amended for better resolution of disputes. However, the IV Schedule shall make the majority of the people believe that justice is only for the rich and they would overlook the benefits of arbitration just because of its expenses. In words of Hon’ble Justice (Retd.) Deepak Gupta, Judge, Supreme Court of India, “if real justice has to be done, then the scales of justice have to be weighted in favour of the underprivileged”.

- FIR Copy of Mahatma Gandhi assasination case

- Licito Concurso'20

- Rules for Licito Concurso '20- A National Legislative Drafting Competition

- Registration Form for Licito Concurso-20

- www.apexcourtweekly.substack.com

- www.lawupdater.com/wp/

- XIIIth K.K. Luthra Memorial Moot Court Competition 2017

- President of India Presented with the First Copy of the Book Statement of Indian Law Published by Thomson Reuters