Article

Resolving The Issues Arising Out Of FDI Norms Governing E-Commerce Sector In India

On 26 December 2018, the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade [“DPIIT”] had issued Press Note 2 (2018 Series) which introduced a series of changes in the FDI norms in the e-commerce sector. 1 In this article, Mayank Udhwani argues that the changes which are introduced by the Press Note go against the very purpose of their introduction as it leaves every stakeholder in a worse off situation by allowing easy circumvention.

-

Mayank Udhwani

Mayank Udhwani

PRIMER ON FDI IN THE E-COMMERCE SECTOR IN INDIA

FDI in India is governed by the Foreign Exchange Management (Transfer or Issue of Security to Persons Resident Outside India) Regulations, 2017 [“TISPRO Regulations”]. The TISPRO Regulations lay down two routes of investment in India: Automatic Route and Government Route. 2 Under the Automatic Route, an investment can be made without seeking approval from the government, whereas the approval of government is the sine qua non of investment under the Government Route. 3 Further, the extent of investment in any sector is subject to the sectoral caps provided under Regulation 16 of the TISPRO Regulations.

https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_FemaNotifications.aspx?Id=11496.

2. Regulation 16(A), vide Foreign Exchange Management (Transfer or Issue of Security by a Person Resident outside India) Regulations, 2017 [“TISPRO Regulations”].

3. Id.

FDI in the e-commerce 4 sector is governed by Regulation 16.B (SL No. 15.2) of the TISPRO Regulations. Regulation 16.B (SL No. 15.2) classify e-commerce entities 5 into two models: marketplace-based model and an inventory-based model. Under the first model, the e-commerce entity acts as a platform between the buyers and the sellers and it does not exercise ownership over the goods sold on the platform, whereas under the second model, the e-commerce entity owns the goods sold on platform. 6 FDI in the e-commerce sector is placed under the Automatic Route and is allowed upto 100% in the marketplace-based model. Whereas FDI is prohibited in the inventory-based model. 7

There have been multiple allegations against the e-commerce entities (namely Flipkart and Amazon) that they are flouting the provisions of the TISPRO Regulations, thereby affecting the interests of the small traders of India. One such allegation of violation of TISPRO Regulations was that Flipkart was selling products which are owned by its erstwhile subsidiary company WS Retail. 8 Such a practice was alleged to have made Flipkart into an inventory-based model rather than a marketplace-based model. In light of such allegations and to prevent circumvention of TISPRO Regulations, the DPIIT introduced certain changes in Regulation 16.B (SL No. 15.2) via Press Note 2 (2018 Series) dated 26 December 2018 [“Press Note”].

In this paper, the author will highlight the ambiguities introduced by the Press Note and the implications of such ambiguities [Section A]. In the next section, the author argues that the amendment to norms governing FDI in e-commerce are susceptible to circumvention by the e-commerce entities [Section B]. The author concludes by providing solutions to remedy the mischief created by e-commerce entities in India [Section C].

5. The term ‘e-commerce entities’ is defined under the TISPRO Regulations as “a company conducting the e-commerce business”.

6. Regulation 16(B), SL. No. 15.2.3(c) and (d), TISPRO Regulations.

7. Regulation 16(b), SL. No. 15.2.1, TISPRO Regulations.

8. Deccan Herald, “ED probing Amazon, Flipkart over FEMA violations”, available at:

https://www.deccanherald.com/national/ed-probing-amazon-flipkart-over-violation-of-foreign-exchange-law-723890.html.

SECTION A: AMBIGUITIES IN THE CHANGES INTRODUCED BY THE PRESS NOTE.

I. 25% SALES V. 25% PURCHASES

As stated earlier, the TISPRO Regulations prohibit FDI in an inventory-based model of an e-commerce entity. 9 Prior to the release of the Press Note, an e-commerce entity would have been classified as one following an inventory-based model if more that 25% of sales on its platform were affected through one vendor. This implies that if the total sales of an e-commerce entity in a financial year was 100 crores and sale of one vendor was more than 25 crores, then that e-commerce entity would ipso facto turn into an inventory-based model, wherein no foreign investment was permitted. This was a fairly simple threshold to calculate and to comply with. However, the Press Note has made the situation much more complicated.

The Press Note has adopted an extremely convoluted definition of an inventory-based model. The Press Note reads as: “Inventory of a vendor will be deemed to be controlled by e-commerce marketplace entity if more than 25% of purchases of such vendor are from the marketplace entity or its group companies which will render the business into inventory-based model.”10 (emphasis supplied)

A prima facie reading of this provision makes it clear that the Press Note has shifted the focus from the ‘sales of an e-commerce entity’ to the ‘purchases of a vendor’. As per the Press Note, an e-commerce entity will have an inventory-based model if 25% purchases of a vendor are from that platform. This is highly problematic as e-commerce entities will now be required to ascertain the total volume of sales of each of the vendors to ensure compliance with the TISPRO Regulations. The argument that the author is trying to make can be understood with the help of the following illustration:

X, an entity engaged in the business of selling clothes, has the following sales figures from different e-commerce platforms:

| E-COMMERCE ENTITY HAVING FDI | NUMBER OF PURCHASES OF X | % OF PURCHASES OF X (TOTAL= 300) |

|---|---|---|

| Flipkart | 100 | 33.33% |

| Amazon | 150 | 50.00% |

| Shopclues | 25 | 8.33% |

| Myntra | 10 | 3.33% |

| Jabong | 15 | 5.00% |

10. Regulation 16(b), SL. No. 15.2.3 (h), TISPRO Regulations.

As evident from the above table, Flipkart and Amazon are in violation of the TISPRO Regulations as the purchases of X have crossed the 25% threshold as per the new provision. However, it is also clear that Amazon and Flipkart will never be able to assess whether X has crossed the 25% purchases threshold unless Amazon and Flipkart are aware of the sales of X on each e-commerce entity. It is not difficult to see how this is problematic for the vendors as well as the e-commerce entities.

There is an alternate way in which the phrase “more than 25% of purchases of such vendor are from the marketplace entity or its group companies” could be interpreted. The provision could be said to be referring to those vendors who purchase products from the B2B arm of the e-commerce entity and sell those products on the same e-commerce platform. 11 Meaning thereby if one vendor is selling 100 units on Amazon and more than 25 units have been purchased from the B2B arm of Amazon, then it would amount to a violation of the Press Note. Even this interpretation suffers from the difficulty described above and the same can be explained with the help of the another illustration:

X, a vendor engaged in selling water bottles on Flipkart and Amazon. The purchases from the B2B leg of each of these e-commerce entities and its sale on each e-commerce platform took place in a manner described in the table below:

| E-COMMERCE ENTITY HAVING FDI | NUMBER OF PURCHASES FROM THE B2B ARM OF THE E-COMMERCE ENTITY | NUMBER OF UNITS SOLD ON E-COMMERCE PLATFORM |

|---|---|---|

| Flipkart | 25 | 100 |

| Amazon | 100 | 50 |

Now, if we were to adopt the interpretation arrived at above, only Amazon seems to in violation of the Press Note as the purchases of X from the B2B Arm of Amazon is more than 25% of the sales on that platform. However, the question arises as to ascertainment of the breach of this threshold when a vendor is buying the same product from two different B2B entities and selling the same product on different platforms. In such a scenario one begs to ask how is Amazon required to ascertain that X is selling the products which it had purchased from Amazon’s B2B arm. It could be very well possible that out of the 50 products which are sold on Amazon’s e-commerce platform, X is using 25 units which were purchased from Flipkart’s B2B.

Both of these interpretations are problematic for the vendors because they will be required to give details of their sales and purchases on/from all the e-commerce entities with which they are sharing a business relationship. Furthermore, this is problematic for the e-commerce entities as they will be required to change the terms of use with each vendor, thereby pushing some of the vendors away.

Not only this, the e-commerce entities will also be able to get a hold of a lot of data on the quantum of sales of their competitors, thereby allowing them to manipulate their stronghold in the market to the detriment of others. This aspect alone raises a lot of concerns, some of which are highlighted below.

Exploitation of vendor’s data will leave vendors in a worse-off situation

As stated above, there have been allegations that e-commerce entities are circumventing the TISPRO Regulations to follow an inventory-based model. 12 That is, the e-commerce entities, are in a position to sell products owned by them on the platform. At the same time, this platform is also used by independent sellers to sell their products to the customers. Thus, e-commerce entities compete with the independent sellers which also list their products on the platform which is owned by the e-commerce entities. This is problematic because of the data asymmetry which is created by the situation described above.

Evidence suggests that Amazon uses its e-commerce platform to “Amazon uses sales data from outside merchants to make purchasing decisions in order to undercut them on price”.13

13. The Wall Street Journal, “Competing with Amazon on Amazon”, available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304441404577482902055882264.

Furthermore, having ownership of the platform where products are sold by both itself and independent sellers allows Amazon to “spot new products to sell, test sales of potential new goods, and exert more control over pricing.” 14

This can be understood with the help of the example of Pillow Pets, a third-party seller which used to sell stuffed pillows modelled on animals on Amazon’s e-commerce platform. 15 After selling nearly one hundred pillows every day consecutively, the third-party seller noticed that Amazon had started offering the same products for the same price. The only difference was that Amazon gave a better placement to its products on the e-commerce platform. 16 Owing to this, the sale of the Pillow Pets by the third-party seller dropped drastically. 17

This example shows that by using the sales data of third-party sellers, Amazon increases its own sales while assuming zero risk. This practice has the following implications on the competition in the market:

- 1. Amazon is exploiting the fact that its competitors on the e-commerce platform are also its customers. The third-party seller who use the e-commerce platform are not only required to pay Amazon to use its platform but also have to compete with the goods sold by Amazon on the platform owned by it.

- 2. This vertical integration in the form of being a host as well as a competitor allows it to gather a large amount of data. This data can be used for its own advantage, thereby creating a conflict of interest.

Therefore, adopting either of the two interpretations of the “25% Sales” criterion, as described above, would end up legitimizing the data asymmetry exploited by the e-commerce entities hitherto.

Issues arising out of the shift from 25% sales to 25% purchases

- 1. It is evident from the illustrations given above that the Press Note requires the e-commerce entities to undertake an impossible task. This is a clear violation of the legal maxim ‘Lex non cogit ad impossibilia’ which translates to ‘the law compels no one to do impossible’.

- 2. The hardship created by compliance with this convoluted provision would take a toll on the foreign investment in the e-commerce sector, thereby affecting the ease of doing business ranking of India. Furthermore, e-commerce entities will have to bear the brunt of non-compliance of vendors, for which they will be penalized under the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 [“FEMA”]. §13 of FEMA prescribes a penalty of up to thrice the sum involved in such a contravention. Given the large-scale nature of transactions involved, this penalty would easily run up to millions of rupees.

15. Id.

16. Id.

17. Id.

- 3. Even if there were a method to ensure compliance with the new provision, it allows easy circumvention (as will be shown in Section-B of this paper) as a foreign entity can affect its sales in such a manner that its purchases on one e-commerce platform do not exceed the 25% threshold.

- 4. Given that the 25% sales threshold is now longer in existence, 100% sales of an e-commerce entity can be affected by only one vendor without violating the 25% purchases threshold. Illustration: the sales of an e-commerce entity in a financial year were 100 crores, all of which were affected from one vendor. At the same time, the total purchases of that vendor from different e-commerce platforms was 500 crores. This implies that even though the sales on one e-commerce entity amounted to 100%, the purchases only amounted to 20%, which is well below the 25% purchase threshold. Now, this has two implications:

- a. An e-commerce entity having a foreign investment cannot engage in B2C business model. However, based on the aforementioned illustration, a foreign entity can engage in a B2C business model through the e-commerce platform, without de jure being in violation of the TISPRO Regulations.

- b. Such a practice will harm the competition in the market as the e-commerce entities with their B2C arm can, with deep discounts, eliminate vendors selling the same products. 18

II. EQUITY PARTICIPATION

The Press Note proscribes a vendor having an equity participation by the e-commerce entity to sell its products on the platform. 19 What is pertinent to note is that the Press Note only uses the term ‘equity participation’. It does not clarify whether the ‘equity participation’ mentioned therein covers direct or indirect equity participation; and whether there is a minimum threshold of equity participation required to bar a vendor from selling on that particular e-commerce platform. This creates a lot of compliance-related ambiguity, the breach of which could warrant serious monetary consequences under §13 of FEMA, thereby leaving the e-commerce entities in a worse-off situation that before.

19. Regulations 16(B), 15.2.3(i), TISPRO Regulations.

III. CASHBACKS AND NON-EXCLUSIVITY

The Press Note prohibits e-commerce entities to mandate any seller to sell products exclusively on its platform. 20 The author opines that it would be extremely difficult for the regulator to check compliance with this provision. This is because there may be situation that a vendor would only want to sell his products on one particular platform. Given this problem, additional mechanisms will have to be put in place so as to see whether the exclusive availability of certain products is due to coercion by the e-commerce entity or due to the free will of the vendor.

Furthermore, e-commerce entities like Flipkart and Amazon tend to attract customers by selling products exclusively on their platform. An example of this exclusivity the sale of Vivo Z1x and Vivo U10 smartphone models on Flipkart. 21 Furthermore, in order to incentivize exclusive sales, these e-commerce entities usually offer a cashback to the customers. Given the fair and non-discriminatory requirement of the Press Note, the customers will no longer be able enjoy the discounts that were earlier offered on select products. Thus, this provision will have a major set-back for the customers.

21. In re: Delhi Vyapar Mahasangh, Competition Commission of India, Case no. 40 of 2019, ¶21, available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/40-of-2019.pdf.

SECTION B: CIRCUMVENTION OF THE FDI NORMS

In this section, by way of an illustration 22, the author will attempt to show that the Press Note fails to achieve its objective as the circumvention of the FDI norms has become easier.

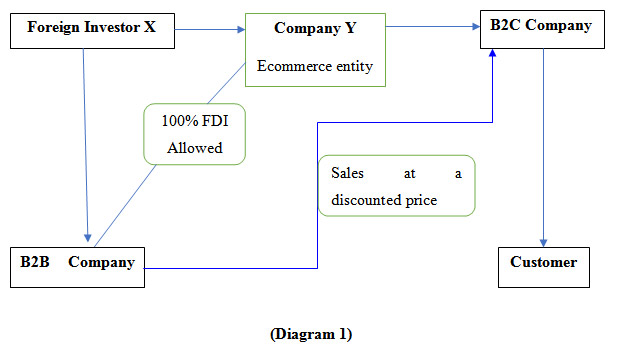

I. PRE-PRESS NOTE SCENARIO AND 25% SALES THRESHOLD

The foreign investor (X) having an investment in the e-commerce entity (Y) would use the platform to sell products through a B2C Company which would be a part of X’s group companies 23. The products sold by the B2C Company were supplied by a B2B Company (Z), which again would be part of X’s group companies, at heavy discounts. It was essential that both the B2B as well as the B2C Company were part of group companies of foreign investor so that discounts could be passed on to the consumers effectively. 24 In such a corporate structure, in order to prevent Y from turning into an inventory-based model, it had to be ensured that the sales of the B2C Company are less than 25% of the sales affected on Y.

23. Regulation 2(xxii) of the TISPRO Regulation defines a group company as: “two or more enterprises which, directly or indirectly, are in a position to (a) exercise 26 percent, or more of voting rights in other enterprise; or (b) appoint more than 50 percent, of members of board of directors in the other enterprise.”

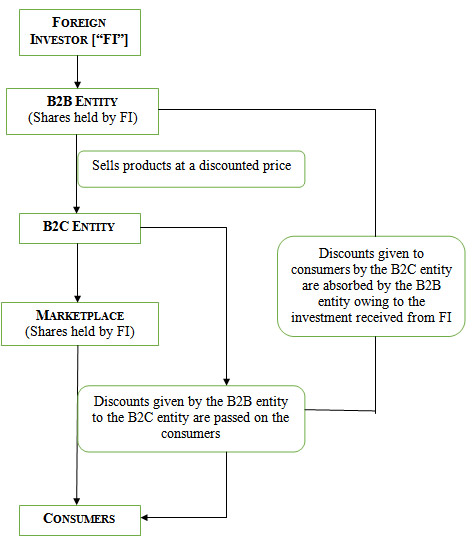

24. Diagram 2 of this Section will explain how the foreign investor employed the practice of ‘deep discounting’ with the help of its group companies.

The rationale for following a corporate structure described under Diagram 1 is that the discounts given by the B2B entity to the B2C entity could be eventually passed on to the consumer. Furthermore, the B2B entity is able to give discounts to the B2C entity as it has the backing of a foreign investor who could afford to absorb the losses incurred by it. The objective of this practice is to gain a stronghold in the market as the e-commerce entity could attract a lot of customers by giving discounts and other lucrative offers while suffering losses. The argument made herein can be understood better with the help of diagram given below 25:

(Diagram 2)

II. POST-PRESS NOTE SCENARIO AND 25% PURCHASE THRESHOLD

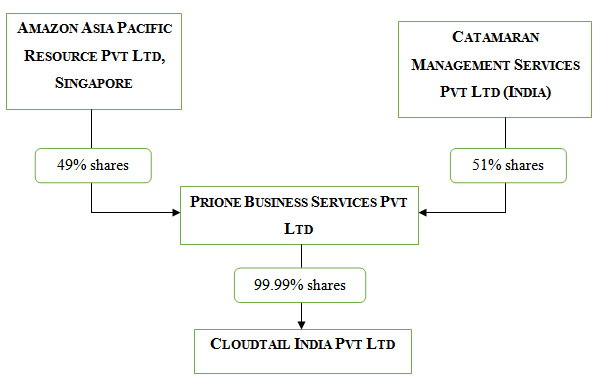

Given the introduction of the 25% purchase threshold and the deletion of 25% sales threshold 26, all that the foreign investor is required to do is to make sure that its investment in the B2C Company does not fall under its group companies. By doing this, the B2C Company will fall outside the ambit of the TISPRO Regulations altogether, thereby rendering all the changes introduced by the Press Note nugatory. This is because the TISPRO Regulations are applicable only to those entities and their group companies which have FDI and will cease to apply if an entity does not have FDI. This point can be explained with the help of changes made in the corporate structure of Amazon 27 two days before the Press Note came into force:

(Diagram 3)

The B2C leg of Amazon was Cloudtail, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of a joint venture (Prione) between Amazon and Catamaran Management (a company owned by Narayan Murthy). Prior to the Press Note coming into force, Amazon had a 49% equity participation in Prione.

27. Rahul Nath Chaudhary, “India’s FDI Policy on e-commerce: Some observations”, available at: http://isid.org.in/pdf/DN1503.pdf.

However, two days before the Press Note came into effect, Amazon brought its equity participation in Prione to 24%, thereby ensuring that CloudTail no longer formed part of its group companies. 28 In this manner, CloudTail become an Indian owned and controlled company 29 over which TISPRO Regulations would not be applicable.

By doing this, Cloudtail can continue giving the discounts in a manner described in Diagram 2 above in an indirect fashion. Furthermore, given the fact that the 25% sales threshold no longer exists, 100% of the sales on Amazon’s e-commerce platform can be made through Cloudtail. Other vendors which also use the platform could be driven out of the market as they will not be able to match the discounted prices offered by Cloudtail, thereby adversely affecting the competition in the e-commerce sector.

SECTION C: REMEDYING THE MISCHIEF UNDER THE FDI NORMS

As evident from the foregoing discussion, not only has the Press Note created a lot of issues which require addressing, but it has also opened a new way of circumvention of the FDI norms which is only going to act towards the detriment of the small retailers. It is without a doubt that the Press Note leaves every stakeholder viz., the brick and mortar enterprises, the retailers using the marketplace-based platform, the e-commerce entities and the consumers in a worse off situation. To quote Star Wars, the Press Note has become the very thing it had sworn to destroy.

In order to remedy the problems highlighted above, the solutions which the author proposes can be classified into two categories: (1) FDI related changes; and (2) Competition related changes.

I. FDI RELATED CHANGES

- 1. Re-introduction of the 25% sales threshold to determine whether the e-commerce entity is following a marketplace-based model or an inventory-based model.

- 2. A clarification is required on the meaning of ‘equity participation’ in Regulation 16(B), SL. No. 15.2.3(i). A minimum threshold of such equity participation is also required to be specified.

- 3. The provision proscribing exclusive deals ought to be removed so as to allow the consumers to continue enjoying the benefits of cashbacks.

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/newsbuzz/cloudtail-india-revenue-up-25-touches-rs-8945-crore/articleshow/71573051.cms?from=mdr.

29. Regulation 14(1)(b) and (e), TISPRO Regulations.

II. COMPETITION RELATED CHANGES

In Section A.I (25% Sales v. 25% Purchases), the author had highlighted how the e-commerce entities by circumventing the provisions of the FDI norms create a conflict of interest by being in the position to exploit the data of the independent sellers which use the e-commerce platform. This problem can be resolved by introducing a ban on mergers that create a conflict of interest.

For e-commerce entities that have reached a certain level of dominance, a ban on mergers that would further entrench their vertical integration could prove to be helpful. It would be a step forward in the recognition that integration across multiple business lines gives rise to a situation where the e-commerce platform can use its infrastructure to the detriment of the competitors that rely on the same infrastructure. Adopting this suggestion implies that the e-commerce entity will not be able to compete directly with its rivals in sectors where the e-commerce entity controls the infrastructure. In context of Flipkart and Amazon, this would mean that these two entities will be prevented from running a marketplace-based platform and selling (both directly and indirectly) on that platform at the same time. These two activities, i.e., retail and platform, would be required to be carried out by two non-related entities, to prevent the e-commerce entities from exploiting the data gained by it as a marketplace-based platform to benefit its B2B/B2C business.

This form of ban on vertical integration is not unknown in the Indian legislative history. Such a ban exists for banking companies, which are proscribed from carrying out any other business other than the business of banking. 30 The Banking Regulation Act, 1949 draws a distinction between the business of banking and other commercial activities. 31 For this purpose, §8 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 prohibits a banking company from dealing directly or indirectly “in the buying or selling or bartering of goods, except in connection with the realisation of security given to or held by it, or engage in any trade, or buy, sell or barter goods for others otherwise than in connection with bills of exchange received for collection or negotiation”. 32

Although the need to avoid these conflicts of interests was recognized in the Draft National e-commerce Policy, 2019, no steps have been taken till date to ensure its implementation. 33 There is no reason why the same analogy cannot be extended to e-commerce entities so as to avoid the conflict of interests which may arise due to usage of common infrastructure in the e-commerce economy of the country.

31. §5(b) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 defines the term ‘banking’ as “the accepting, for the purpose of lending or investment, of deposits of money from the public, repayable on demand or otherwise, and withdrawal by cheque, draft, order or otherwise”.

32. §8, Banking Regulation Act.

33. Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, Draft National e-Commerce Policy- India’s Data for India’s Development, 23 February 2019, Chapter III (A), available at:

https://dipp.gov.in/sites/default/files/DraftNational_e-commerce_Policy_23February2019.pdf.

- FIR Copy of Mahatma Gandhi assasination case

- Licito Concurso'20

- Rules for Licito Concurso '20- A National Legislative Drafting Competition

- Registration Form for Licito Concurso-20

- www.apexcourtweekly.substack.com

- www.lawupdater.com/wp/

- XIIIth K.K. Luthra Memorial Moot Court Competition 2017

- President of India Presented with the First Copy of the Book Statement of Indian Law Published by Thomson Reuters